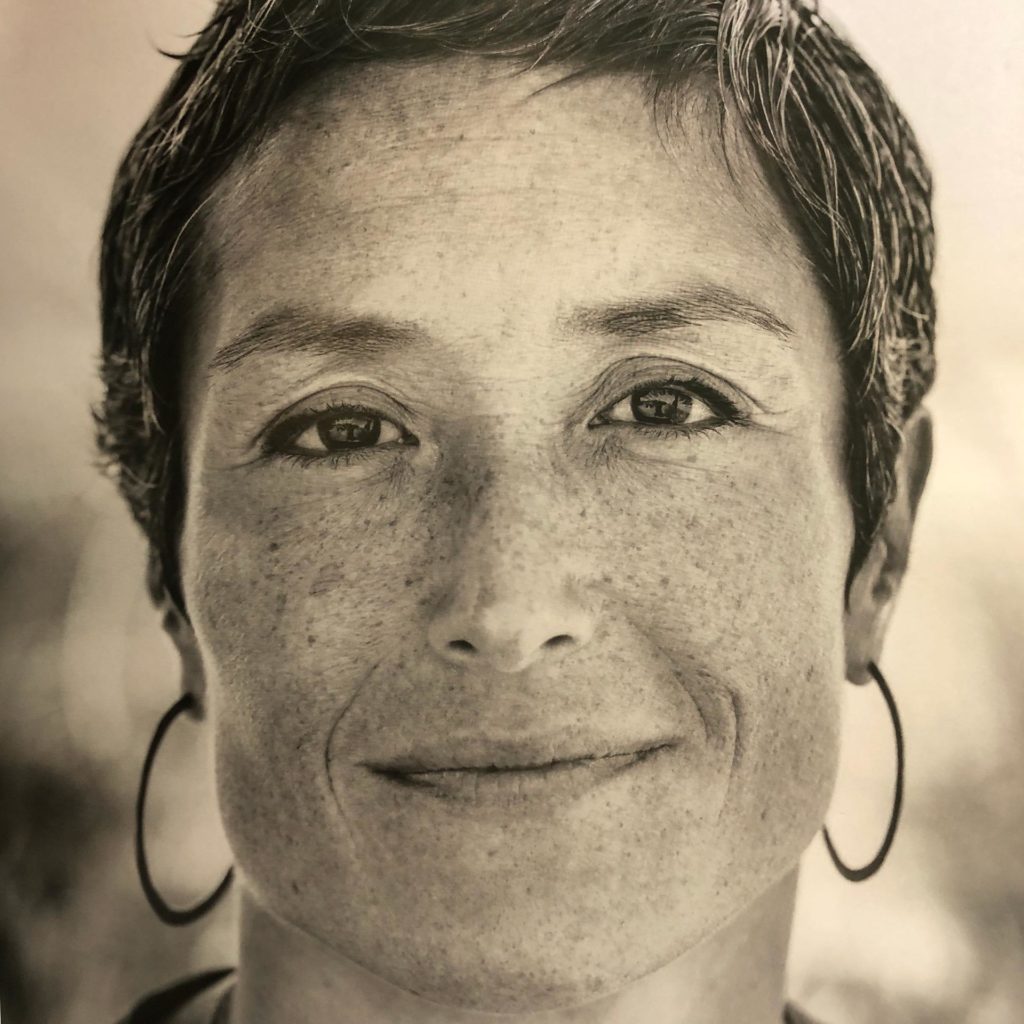

Interview & Words: Elisa Routa

When I was a kid, I would watch the Rocky movie series compulsively and excessively, putting Sylvester Stalone at the very top of the sacred pyramid of my heroes. To me, Rocky Balboa was contributing to social change. So, when I learned Sachi Cunningham worked as an assistant to Barry Levinson, director of Bandits, the 2001-film starring Bruce Willis and Cate Blanchett, I made a promise to myself to watch the comedy-drama film as an ode to my youth, and to my shameful and assumed idols. And I did watch it. Entirely.

“It was a natural progression to go from Hollywood to documentaries,” said waterwoman, photographer and filmmaker Sachi Cunningham who, after a career in Hollywood, committed herself fully to making independent films dedicated to the ocean and women. Because “you can’t be what you can’t see,” Sachi has been creating images of female mentors in a world that’s long been known as pretty male dominated.

Through her films Chasing the Swell and SheChange, award-winning filmmaker and social advocate Sachi Cunningham has been following the big wave seasons and her main players. Today, at age 47, the girl who “used to ask for an ocean in her backyard every Christmas,” has managed to increase the visibility of women in the big wave surfing world, celebrating them as role models. Using her camera as a tool of social change for the last two decades, Sachi’s pioneering work has led her to witness women’s activism, while purposefully opening conversations about global gender-equity in big wave surfing. “They are stories of women unapologetically asking for what they want.” After discussing inclusion, equal access, equal opportunity, pay parity and her fight for gender equality, I revised the hierarchy of the pyramid of my idols. Rocky sits side by side with Sachi now.

│

“Big wave surfing is this tribe within a larger tribe. I’ve always felt at home in it because they are all crazy people like me.”

│

You began swimming when you were four and started competitively swimming from age seven until college. After that, you played water polo for four years. Tell us more about the importance of the ocean in your life…

I was a bodysurfer from a young age. I actually learned how to shoot waves before I learned how to surf a wave. When I started learning how to surf, I was terrible but I knew that I could get out and swim in those waves. I definitely couldn’t surf in them but watching other people surf is a good way to learn how to surf. What I remember is not being able to stand up. It took me like three months to just stand up. It was very frustrating because I feel like I’m a natural athlete in a lot of different sports but I was not a natural surfer. Above all, I like the challenge so that’s probably why I stuck with it.

_

You’ve been introduced to the ocean even before surfing, then you introduced your own daughter to the ocean… Is it important for you that she knows the importance and benefits of the ocean?

I’ve always been a water baby and my daughter has been taking swimming lessons since she was born. It’s been very important for me to have water and the ocean as an outlet for her emotional, creative and physical development. It’s much more than an athletic outlet like it has been for me. I knew the first time she went in the water that she was a water baby too. You just can see the transformation on her face and her expressions. Everything changes as soon as she touches the water.

_

When did you get hooked on water surf photography?

To get into water photography and to professionalize my passion for surfing was always something that I was discouraged from by my father, but what has been encouraged by him is to have a passion, to follow it, to work hard and to be the best at whatever I chose to do. I’m often envious of people who know exactly what they want to do and are so focused from the start of school. My college roommates were these kinds of people; they knew what they wanted to do. They wanted to be doctors, so they went to school to become doctors and they became doctors. I really admire people who have that focus. I never really had that focus because I loved too many things. I’m kind of a jack of all trades. At this point now, as old as I am, I think it’s actually been my strength. Having that diversity has helped me professionally.

│

“Hollywood was definitely a formative experience. It has its own tribe, a tribe of creative people, just like surfing is.”

│

You’re both a teacher, a photographer and a filmmaker today. You worked for ten years in the Hollywood film industry. It sounds like a completely different world…

It is and it isn’t. Hollywood has its own tribe and it’s a tribe of creative people, just like surfing is. It’s a traveling circus of creative people so I would say it’s not so unlike surfing. Working in Hollywood was a lot of fun, it was exciting to work with big stars like Bruce Willis and Cate Blanchett. I was an assistant to director Barry Levinson and I was Demi Moore’s assistant for a while so that was super fun. I was working on a set of a film called Bandits. Bruce Willis was one of the stars and, on the first day shooting, he gave Barry this new thing called a digital camera. Barry handed it to me and said, “Figure out how to use this and start taking pictures behind the scenes.” Bruce Willis saw me doing that and saw how much I was enjoying it – and probably taking some decent photos – so he handed me his video camera and said, “Start shooting video behind the scenes!” I started shooting video behind the scenes and I think that really liberated me. I was getting tips on shooting from Dante Spinotti who was the amazing DP. Being able to have that camera, having the power to tell the story, having basically that whole crew in my hand… Doing all that and making all those decisions myself was very liberating. I also think a large part of why I didn’t stay in Hollywood is that I never really had films in my head that I wanted to make, even when I knew I wanted to go into films. I majored in History as an undergraduate at Brown University because I knew that I wanted to tell stories through films but I didn’t necessarily have them coming out of my brain. I studied History so that I could start collecting stories that actually happened. I think it was a natural progression to go from Hollywood to documentaries because I saw a light. It was a series of things but Hollywood was definitely a formative experience.

_

In 2011, you presented your documentary Chasing the Swell. Can you reminisce on how the film was made?

I made that film because I had a full-time job as a video journalist at the Los Angeles Times. I was part of the first video unit that was assembled at the Los Angeles Times. As soon as I was hired I made it known that I wanted to focus on stories about the ocean and the environment. I had a unique skill, it was the ability to shoot in the water. So I would shoot everything from stories about Olympic water polo players to the oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico to this Chasing the Swell story. I don’t get seasick… These are the things that I kinda take for granted but not everyone can do that so it’s also something I try to emphasize with my students. “Find what you’re good at and what will make you stand out.” That was one of the things I would emphasize when I go to the Los Angeles Times. 50% of our stories were assigned or based on reporting that other reporters were doing, and then about 50% were enterprise stories that we pitched ourselves. Chasing the Swell is something that I pitched as a longer project. The Los Angeles Times basically let me loose. Over the course of the project, I had other projects going on but they gave me the budget and freedom to do that story. And I did it almost entirely as a one-person-band, shooting, producing and editing. I had a lot of people helping me with the editing and the post-production. When I could I had some people helping with the shoot. It took about a year.

│

“[ Big wave surfers ] have a lot of energy because of the amount of power and energy that they surf on. I think it goes through you, it enters you, I don’t think it’s something you’re just gliding on.”

│

Chasing the Swell is a surf video in three chapters, following some of the world’s top big wave chargers like Greg Long, Jeremy Johnson, Mike Schlebach and James Taylor. Tell us more about the big wave community you’ve been part of for so long.

I think it’s a very special community. It’s this tribe within a larger tribe. I’ve always felt at home in it because they are all crazy people like me. The kind of profile of a big wave surfer is someone who has many years of being a waterwoman or a waterman, who has lots of water experience and a lot of ocean knowledge. They have to train all year for those moments so I find that they’re very disciplined in their training, hard-working because they have to be ready in that one moment to jump into a 15-foot wave, and extremely smart. They also have to be weathermen and women, they have to be weather forecasters, they have to understand. There’s also more consideration towards the equipment because you have tow boards, you have longboards and jet skis, you have to learn how to rescue people so there is water safety involved. It’s more the holistic lifestyle for me. I know how surfing is a lifestyle but the big wave surfing lifestyle suits me. I just gave you the profile of their work ethic and knowledge, but I also think they are often incredibly fun and have a lot of energy because of the amount of power and energy that they surf on. I think it goes through you, it enters you, I don’t think it’s something you’re just gliding on. It’s something that comes into you and I think any big wave surfer has an extra fire in their eye that I see and that I’m in love with.

_

Over the years, you focused your work on helping women and the female big wave surfers in professional big wave surfing reach gender equity on the world tour. Tell us more about your fight…

When I made Chasing the Swell, there were very few women in the water. What changed since then is that in 2014, there was an invitational at Mavericks called the WickrX Super Sessions. It was the first time I’d swam in the water at Mavericks to shoot. 14 women came around the world for this event. Among those extremely talented surfers were Paige Alms, Andrea Muller and Keala Kennely. They were really good and they very much stood out as having the potential to be equal with the men, to be provided the same opportunities and the same spotlight. As a female filmmaker, I saw a lot of parallels to what the women were trying to do – which is to be the best big wave surfers they could be – with what I was trying to do. I faced the same challenges in that industry. And I still do today. They were trying to be the best big wave surfers in the world while I was trying to be the best filmmaker I could be. There weren’t necessarily the same opportunities for all of us to develop these skills, elevate those skills and showcase those skills. I just started following them with a camera because nobody else was. I wanted to tell their stories because nobody was. As far as I could see, it was the most important story to be telling.

│

“It was more challenging for a woman’s story to be told, and for a woman to tell a woman’s story, I’ve got in some ways a double penalty. I also think it is the strength of the project.”

│

And that’s what you did with the SheChange film Project. You’ve been following a crew of female chargers like two-time Big Wave World Champ Paige Alms, San Francisco charger Bianca Valenti, big-wave surf pioneer Andrea Möller and big wave warrior Keala Kennelly. Can you tell us a bit more about this movie?

After Chasing the Swell, I was looking for my next story. I had always told myself that I was not gonna do another passion film project unless I had funding. But unfortunately I have not paid myself at all for this and I put a lot of money into the project. It is very much a passion project still. When I started fundraising, I was looking for ways to finance the film and everyone’s first comment was “What about their sponsors?” None of them had sponsors at the time. They do have sponsors now, but back when I started, they didn’t. It was more challenging for a woman’s story to be told, and for a woman to tell a woman’s story, I’ve got in some ways a double penalty. I also think it is the strength of the project.

_

Fighting for gender equity in big wave surfing, do you consider yourself a social advocate?

Yes for sure. I got into journalism because I wanted to tell social justice stories, issues of race, class and gender and so that’s also why I had to do it. This story contains everything I’ve worked my entire life for. It has all of my passions in it; it’s the social justice issue, it’s the big wave surfing, it’s my water photography, it’s historic, there’s a journalistic importance to the story. I feel it’s the combination of my life and work.

│

“Equality is something that America prides itself on being all for but not everyone is holding people accountable for that. Through my stories, I’m hoping to create gender equality and change the way people think about women in the water.”

│

In the film, some female surfers tend to break the gender barrier, a mission that has also been undertaken by the Committee for Equity in Women’s Surfing (CEWS) supporting equality, inclusion, equal access and pay parity. A few words about the Committee?

I actually would have loved to join the Committee but as a filmmaker and journalist, ethically I needed to stay a step removed so I could tell their story rather than be the story. I feel that my goals as a filmmaker are the same as theirs. Through my stories, I’m hoping to create gender equality and change the way people think about women in the water, and they are trying to change that through policies. They’ve been able to collectively form a political block that is stronger than just one of them because they are such powerful and successful women in their sports.

The Committee was co-founded by San Mateo County Harbor Commissioner Sabrina Brennan, she really started it all with professional surfers Paige Alms, Keala Kennelly, Andrea Moller, Bianca Valenti and Lawyer Karen Tynan. They have everything they need, they have the players, the politicians and the lawyers. Very wisely and smartly, they went through legal channels and policy channels, rather than trying to bash our heads against the wall for another 100 years trying to make men change or trying to make society change the way that they think about women. The Committee actually noticed that these laws and policies already exist and if we just use them to our advantage, we can create change. That’s what they were able to do. They’ve been specific to California law but now they’re seeing that some of those laws exist in Hawai’i. Equality is something that America prides itself on being all for but not everyone is holding people accountable for that. The Committee was able to finally hold governments and all of the players accountable for that equality.

│

“My mum is Japanese-American, she was born during World War II in an internment camp. Today, I’m still trying to unlearn my Japanese cultural voice that says to just be quiet. My goal is to use the art of storytelling to raise my voice and have an impact to do it in a thoughtful way.”

│

On Sept 5, 2018, the WSL announced equal prize money for every WSL controlled event, including the 2018/2019 Mavericks Challenge, in the 2019 season and beyond. This made the WSL the first U.S.-based sports league in history to pay their male and female athletes equally. That was a true victory. According to you, is standing up for our rights and making our voices heard are always a good idea?

Yes. My mum is Japanese-American, she was born during World War II in an internment camp. She’s spent the first four years of her life behind barbed wire. The whole community of Japanese-Americans – obviously not everyone but for the most part – that were imprisoned were very much told to not raise their voice. “The nail that sticks out gets hammered down. » It’s a phrase in Japanese that means just do what they tell you to do, be a model citizen, don’t complain, don’t raise your voice and keep your mouth shut. Having seen what happened when drama breaks in silence and what happens when you don’t raise your voice, I know that’s why I got into storytelling. My goal is to use the art of storytelling to raise my voice and have an impact to do it in a thoughtful way. Today, I’m still trying to unlearn my Japanese cultural voice that says to just be quiet but I do think you have to ask for what you want. That’s what attracted me to these women and their stories. They were so unapologetically asking for what they wanted. I think as women worldwide, we are not all encouraged to do that. As a teacher (Professor of Multimedia Journalism at San Francisco State University), I know that. It’s always the students that speak that get what they want. I’m learning from my students and from these women.

│

“My work has been trying to offer role models and images of women in the water so that other young women could be what they can see. You can’t be what you can’t see.”

│

│

What would be the solutions for a more inclusive surfing industry?

The main solution is to have more women in the water. My work has been trying to offer role models and images of women in the water so that other young women could be what they can see. You can’t be what you can’t see. When I was starting this, there really weren’t that many images of women out there. Now, with the WSL streaming, now with equal pay for the women, I have no doubt that it’s going to massively change. I already see it in the big wave world, there’s already this group of young women going out there. They only need to be encouraged, have mentors and role models. Just the exact opposite of most of the women and what I have experienced in the past. Now there’s this clear path of where to go, the road is wide open. I can’t wait to see how much it’s gonna change. I know it will.

_

Justine Dupont recently won the Nazaré Tow in Challenge in Nazaré in February 2020. How do you see the next generation of female surfers and what would be the message you’d like to share to them?

I would just say to go for it and support each other. That’s not only important but that’s also just the most fun.

Gender isn’t an issue but I think we’re still at the early stages so as much as we can mentor each other and help each other… That’s the goal.

│

“I saw this little orange cap in the water. I grabbed the binoculars, looked and… “That’s a woman!” The fact that she was a woman was everything. At that time, it was this point of access.”

│

In your film, Keala once said: « “Call us the badass, big-wave bitches ». Our section “And I did it anyway” pays tribute to the badass stories. Which female surfer, female surf filmmaker or artist do you look up to and why?

One person that had an early influence on me is a bodysurfer at Ocean Beach named Judith Sheridan. She was pictured in Dear and Yonder, the film that came out a while back. She has a disability and she’s not the one you’d consider a traditional surfer from the local surf culture, or what people think a Californian surfer is like. Judith is a scientist, a doctor, a PHD, and she’s this amazing athlete. She was out there surfing big waves, pioneering at Mavericks then at OceanBeach long before I was. Actually, the first time I went bodysurfing at Ocean Beach, she was out there. I went out because I saw her out there. At the time, I didn’t know how to surf very well and I wasn’t confident on a surfboard but I was confident bodysurfing, but I was new to Ocean Beach, back in 2001. It was this big and intimidating surf so I wasn’t entirely sure that I could do it. I saw this little orange cap in the water. I grabbed the binoculars, looked and… “That’s a woman!” The fact that she was a woman was everything. At that time, it was this point of access. I don’t think I would have easily gone out if it was a guy. I thought, “Okay so I can do that too”. Then, she taught me everything I know about swimming at Ocean Beach. She actually likes to tell her story from her perspective, people are always asking her to take them out and teach them how to swim at Ocean Beach. She’s like, “You’re the only one that swam out to me.”

_

What’s up next for you?

Usually, I do a video every year with the Surfrider Foundation. I like working with non-profits like Surfrider to spread messages not only about surf, but about the ocean and health. So there’s a little project that’s coming out. I did a film with Belinda Baggs, Liz Clark and Moona Whyte this Summer in Indonesia for Patagonia. That’s just a short film and that should be coming out any day now. Then, I’m taking a sabbatical year as a teacher next year, starting mid May, I’ll be on a year long sabbatical where I’ll be able to concentrate on finishing shooting. So I’m just trying to do the final fundraising for SheChange.